|

|

|

BT announces record return-to-work rate after pregnancy Wednesday, September 28, 2005 BT announces record return-to-work rate after pregnancy ~~~

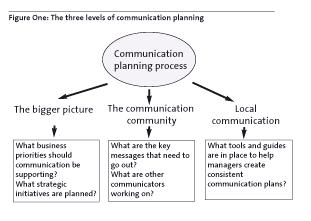

The 12 rules for creating successful business-charity partnerships ~~~ Developing a consistent planning approach Monday, September 26, 2005  Developing a consistent planning approach Cutting out message overload, repetition and inconsistency By Bill Quirke and Richard Bloomfield The complexity and frequency of communication taking place in many organizations can have dire consequences for the target audience, namely employees. Key messages get drowned out by trivia, repetition bores the audience, and inconsistency undermines trust and credibility. Here, Bill Quirke introduces the "air traffic control" approach to managing and prioritizing the many layers of organizational communication. There's an old saying that to "fail to plan is to plan to fail." Corny as it may sound, this is a salutary reminder that as communicators we can't rely on last minute inspiration if we really want to deliver results. On the other hand, John Lennon reminded us that "life is what happens when you're busy making plans." Which brings me to my point: the secret to successful communication planning is getting the balance right. The communicator who focuses on reams of beautiful communication plans will fall victim to analysis paralysis, hypnotized by all the interdependencies. On the other hand, whoever plans on the proverbial cigarette packet will eventually lose all sense of strategic direction. Key areas to focus on: In our experience, successful organizations plan communication at three levels: 1) The bigger picture - ensuring that communication is supporting the priorities for the business, and that key strategic initiatives are "on the radar." 2) The communication picture - clarity about the key messages that communicators must get across, what other communicators are planning and how can they work together better to reduce the risk of duplication and confusion. 3) The local picture - specific projects and initiatives - helping ensure that project managers use the same approach to communication planning, so that local activity can be prioritized and coordinated. Before we look at these three areas of focus in more detail, let's revisit why planning is such an important part of the communicators' toolkit. Why planning is important Planning is high on the agenda for effective communicators for a number of good reasons. Communication directors are tired of having to keep a wary eye out for unexpected and unwelcome communication from within their own organizations. It's hard enough trying to cope with a volatile external environment without fearing you may fall victim to the "friendly fire" of unplanned internal communication. Global heads of communication want to ensure that they've got a coordinated picture of what's going on in individual countries and divisions and functions. For their part, individual countries don't want to have unexpected, time-consuming, and inappropriate communication initiatives dropped on them out of the blue from the global center. In matrix organizations, the number of communicators seems to increase geometrically. As soon as one baron within the business hires their own communicator, the air quickly becomes thick with newsletters, mousemats and roadshows. Large change programs with large budgets enable gifted amateurs or outside consultants to engage in "check book communication," in which they can buy share of voice by out-spending their more constrained colleagues in the corporate communication departments. Communication overload Organizations are waking up to the fact that while internal communication is a good thing, you can have too much of it. They're shifting from an informal competition between various communicators to creating greater collaboration that allows the company to present a more coherent face to the business. Employees continually complain of initiative overload, while functions at the center, change initiatives in the change program office, and the global chief executive's office all pursue what we call "flat pack communication." This is where the employee receives communication from all corners of the globe, without any coherent picture about how it's all supposed to fit together. They're forced to bolt bits of communication together in the hope of building a coherent picture. No wonder the final result looks skewed. Organizations are now waking up to the need for far greater coherence - so that each piece of communication reinforces rather than contradicts others, and that all stakeholders get a consistent picture. Getting that degree of coherence and consistency in complex organizations demands careful planning and collaboration between communicators. Inconsistency undermines credibility In external communication, inconsistent messages undermine brand and reputation. Internally, different and inconsistent communication can unnerve employees and reinforce their suspicions. In times of change, employees look for the signals to indicate what could be the real agendas of their leaders. Employees become "Kremlin watchers" watching every nuance of communication from each of the leadership team to find out where the splits are, who's in and who's out, and what's really happening. Inconsistent messages from the top team can signal splits and fuel conspiracies that are often based on simple misunderstanding. Most organizations now understand that the barrier to effective engagement of their employees isn't the amount of budget left to stage roadshows, or indeed the number of trees left from which to make newsletters. The real scarce resource is the amount of time and attention they can get from their people. Unless the organization is clear on its priorities and focused in what it says, people will tune out. More and more organizations are finding that far from generating greater illumination, increasing communication actually creates inconsistency, confusion and clutter. So what can practitioners do to improve the planning process? The following steps will help reduce message overload and inconsistency. Step 1: The bigger picture The first step entails looking at the bigger picture. At this level, organizations want to: • reduce volume and eliminate duplication; • make sure that what goes out is high quality and coordinated; • allow space for people to make sense of the messages they receive; • ensure that key messages get the most airtime. This means greater prioritizing and reduction in the quantity of messages. Doing this involves a process of what we call "Air Traffic Control." This is a process for plotting what's on the business agenda, identifying the relative priority of different initiatives, and mapping who is likely to be affected by them. Air Traffic Control then allocates time and space to planned communications according to how important they are to the business and their priority, rather than who can shout the loudest. This introduces an element of co-ordination and control of internal communication, and reduces the number of unexpected or unannounced, high-impact initiatives. Step 2: The communication community At this level, the organization should: • agree common approaches for communicators; • agree priorities and key messages; • coordinate communication from different parts of the business. While communicators should respond to the specific needs of the part of the business in which they operate, they need to do so in a common and consistent way. To enable this, the organization should establish common approaches, principles and standards for communicators to follow, and create opportunities for practitioners to get together and exchange best practices and ideas. Step 3: Local projects and initiatives One stage on from ensuring that practitioners are working to the same patterns and approaches, is to try to standardize the way that communication is planned to support projects and initiatives. As many communicators will know, getting some project managers to even consider communication before the closing stages of their project can often be difficult. For many project managers, communication is an activity they can leave to others. When this happens, it tends to be last minute, rushed and half-baked. We've found that project managers are far more likely to consider planning communication for their project or initiative when they can see that there's a clear and simple process. For some clients, this has meant developing an online planning tool, which takes project managers through the key stages in a communication plan, and allows them to produce high quality plans that reflect the standards and processes of the organization. Developing a common language In today's fast-changing business environment, communicators cannot afford to fly blind. They need planning processes and disciplines to help them avoid overloading the organization and to make sure that communication activities are focused on the right business priorities. In summary, getting more out of communication in terms of coherence, clarity and credibility requires the coordination of activity at three levels: strategic messages focused on business priorities; messages from communicators working across the organization; and messages coming from managers working on local projects and initiatives. Without some kind of common planning framework and process in place, it's difficult to manage the different agendas and communication priorities of individuals. Having a common planning process helps ensure a common language, greater consistency and easier comparability of plans. Planning should aim to reduce: 1. Unexpected and unwelcome communication from various people within the organization. 2. Time-consuming initiatives from the corporate center that haven’t been planned or prepared for locally. 3. An overload of messages with little strategic relevance, that drown out more important key messages. 4. Communication that leaves employees with an inconsistent or incoherent picture of the organization’s business priorities. 5. Poor quality communication coming from managers without acces to planning guidelines and tools. ~~~

Identifying the real value of communication

How can communication add value? How do you make a stronger link between business payoff and communication investment? How do you link together different components of communication so that it all adds value as a whole rather than individual parts working against each other?

increased cost of administration; and high employee turnover.

Improving the quality of information – clearer messages written in shorter, plain language - Improving the capacity of existing communication channels, for example by using face-to-face meeting time for something more valuable than just information exchange. Reducing the amount of information going out by limiting the number of producers of messages and limiting their accesss to communication channels - Stopping central production and taking an advisor role to help managers achieve their objectives. Where communicators can't get involved in the business strategy they can still add value by improving the efficiency of communication processes and reducing costs – something that usually gladdens the finance director's heart. Most communicators have to combine the roles of strategist and advisor with that of crafting and drafting – good business strategies are useless if they can't be clearly articulated. For example, an organization that we worked with had an absenteeism problem. We recognized that the company was putting out streams of management speak and employees simply didn't understand about the impact absenteeism was having on the business. Simply by improving the clarity of writing, communicators were able to help employees become more engaged in company business and more interested in work. Absenteeism went down.

~~~ Practical Negotiation Principles By Larraine Segil and Avi Goldstein The need to resolve issues and craft agreeable solutions, usually through some form of negotiation, is at the core of much organizational communication. Although the situations giving rise to these workplace encounters differ widely, familiarity with basic negotiation skills will improve the chance of securing a fair and workable solution that satisfies all parties. The word "negotiation" often conjures up images of international treaties, corporate mega-deals or the purchase of a used car. What's often missed is the subtle negotiating we all do on a regular basis. The everyday agreements we reach in cooperation with those around us. The informal influence we exert to make decisions and get things done. And even the deliberate framing of messages in which the goal is to induce some change in attitude or behavior. Although not as formal or structured as what most people think of as negotiations, these day-to-day encounters could well be considered in the same category. No matter the context, medium, or formality of the situation, whenever we are attempting to arrange or settle matters by some level of mutual agreement, an application of key negotiation principles will help make our communication more effective and our interactions more productive. Over the course of more than 20 years of consulting on organizational and individual negotiation capability, we've found the following guidelines for negotiation particularly helpful. Test your assumptions Assumptions drive results by shaping our actions and goals. As you engage with your counterpart, consider what assumptions you might be making. For example, key facts that you are taking for granted, conclusions that you're reaching, motivations that you're attributing to your counterpart, and the goals that you're aiming for. How are these assumptions influencing you and your counterpart's behavior and communication? What might each of you do differently if one or more of your assumptions were proven incorrect? In action: As you consider and clarify your own assumptions, ask questions to clarify the assumptions that your counterpart is making, testing to see how your assumptions line up with theirs. Jointly explore differences in assumptions, and their reasons and implications. The time taken to clarify and align assumptions will help to avoid the frustration caused by disconnects lingering below the surface of a conversation or negotiation. Pay attention to process Negotiators and communicators alike should pay attention to the process they employ to reach their goals. The process - how an agreement is reached - is often as important as what the agreement might be, i.e. how something is communicated is often as critical as what is being communicated. A good process improves outcomes by enabling constructive engagement, promoting clarity and nurturing relationships. This is especially important when dealing with complex issues; when an ongoing relationship is involved; or when the cooperation of a counterpart is necessary to implement an agreement - all very common conditions. In action: Explicitly consider the series of activities you will engage in as you go about your negotiation. What do you need to do to prepare? Who needs to be involved at various points? How will you engage with your counterpart? What information will you share? Who needs to be informed of the outcome? Such considerations of "process" don't have to be overly complicated, but they should be methodical and systematic. Foster two-way communication Driving results is an uphill battle when communication styles tend toward delivering directive messages. In today's complex organizations, unilateral persuasion is simply not a sustainable option for effective communication. Rather, communication must be informed by a mindset of engagement and modesty - a willingness to explore, learn and problem solve, rather than explain, instruct and pronounce. In action: Balance advocacy and inquiry as a communicator. Don't just explain your view; ask questions to clarify your counterpart's as well. Doing so will lend interpersonal interactions a constructive spirit of creative, joint problem-solving, helping you to discover and create new value while building closer relationships. Separate people from problems Relationships often get tangled up in negotiations and sensitive communications. One of the best ways to preserve and improve relationships while solving difficult problems is to separate one from the other, and to be unconditionally constructive on both. That doesn't mean that one ought to be soft on the problem at hand. On the contrary, the problem should be attacked directly and firmly, but as an entity distinct from the people involved. In action: Discuss any salient people issues explicitly, but separately, making sure not to confuse these issues with the substance of the problem at hand. Never try to fix relationship problems with substantive concessions or vice versa. Be uncompromising in your separation of people from the problem. Explore interests, not positions Clarify and prioritize interests (needs, concerns, fears - "why"), as opposed to positions (offers, demands, requests - "what" or "how"). Consider what your interests are and what your counterpart's underlying interests might be. By exploring and discussing interests instead of positions, you'll be able to come up with a wider range of possible options for agreement and, very likely, discover more value than by haggling over opening positions, concession by concession. In action: Identify which interests you share, which are competing, and which are simply different. If you encounter positions or demands, ask "why?" or other open-ended questions to get to the root of each position. Think of ways to take advantage of shared or complimentary interests and ways to mitigate the effect of competing interests. Employ objective standards Objective standards ought to be employed as both swords and shields, to help support reasonable options for agreement and to protect against options that would be unhelpful or even detrimental. To build your arsenal, brainstorm objective standards and collect supporting data to help choose impartially from among possible options. Make sure you introduce relevant standards during the course of negotiation. Standards produced as validations of an already made arrangement are not very persuasive and in some cases might feel excusatory or coercive. Rather try to introduce criteria that both parties can use to make a choice. In action: Look for existing standards (for example, precedents, studies, market data, industry practices, etc.) as well as standards you could generate (for example: third-party testimonials). Avoid preparing standards that support only your perspective; consider what objective standards would support your counterpart's perspective as well. See agreement as the beginning Consider the boundaries of what you are willing to commit to with an eye to the future. Remember that agreement is just the beginning. Soon after your signature, handshake or verbal OK, you or someone else will be responsible for acting on or adhering to the agreement. To make sure that any commitments made are clear, realistic and operational, make a list of implementation issues or topics to discuss before commitment, and discuss the procedure by which agreements will be implemented. If necessary, consider different, gradual levels of commitment (a follow-up meeting, a tentative agreement in principle, etc.). In action: Be clear about what level of commitment you are seeking from your counterpart. Are you looking for a firm deal or just exploring options? As you near commitment, make sure you consider who's going to be impacted by your agreement and consult or inform (or even negotiate with) them as appropriate. Set the standard The role of communication professionals is to be a standard-bearer of the skills of good internal and external messaging. Approach interactions and the construction of messages, both formal and informal, with these principles of negotiation in mind. This will enable you to carry that standard both for the relationships that you manage every day within your organization, as well as those in which you are representing your organization. Top tips for Negotiation: 1. Consider and clarify your own assumptions as well as those of your counterparts. 2. Agree on a process to follow to give negotiations a clease sense of purpose and direction. 3. Think about who else needs to be involved in the negotiation process. 4. Make sure that the problem at hand is dealt with separately from people-related issues. 5. Be inquisitive: try find out what it is your counterpart is trying to achieve and why. 6. Be clear about the unspoken interest or outcomes that could influence negotiations. ~~~

Workers pressured to let ethics slip One in four These were the key findings of Ethics at Work: a national survey by Simon Webley, research director of the But other results were more encouraging: around 80 percent of In the Source: Ethics at Work, published by the ~~~ How to prepare for a focus group By Angela Sinickas You're considering staging a series of focus groups. Your organization is in the early phase of an environmental assessment that will have it polling employees for their opinion on a variety of performance-critical topics. The focus groups will start the ball rolling. What do you do to prepare? Focus groups can serve a host of purposes, of course. Like panels filled with consumers asked to give advance feedback on some new product, employee focus groups can be a remarkably effective way to test-market key messages or communication strategies. They can be an effective way for communicators to put their ears to the ground and listen for what employees will say when asked open-ended questions. They can also be effective lead-ins for surveys in the early stages of development. For organizations facing serious performance issues, focus sessions are a useful means to lay the groundwork for asking the right questions in a way calculated to produce the best data. 1. Where to start Start where any good consultant starts - with the client. Is there a principal figure (or group) in the organization asking for the data? If so, find out as much as you can about what has prompted the request. Educate yourself about the problem lying behind the request. You may find yourself talking with the CEO, or with the director of a division. Schedulean appointment and be clear about its purpose. Before you go, prepare a checklist for yourself detailing the ground you want to cover. 2. What you need to know Remember that you may not always get the information you need on the first try. Consider the questions to ask again from another perspective. Above all, listen. What are the specific goals the client has in mind? Does the client have a pre-determined view of the outcome? Probe for the trouble spots, if there are any. What are you likely to hear about? 3. Find out who else you should speak to Who else in the company, or division (or whatever the organizational unit that's to be the focus of the research) will have useful information to help you prepare? It may be a senior manager, or someone who's a long-time veteran of the organization. You may find yourself conducting several one-on-one interviews to help round out the picture. If you're a recent arrival in the company, consider whether anything else in the organization's history might be useful to know. Has the problem or issue occurred before? Has the program been tried earlier? 4. And now for the sessions.. Now that you've developed the background and sounded out the client, think ahead to the session (or sessions, if there's to be a series). Who should be there? How large should the sessions be? How long should they last? Where will they take place: off-site or in-house? Will they be open to volunteers? How many do you want to convene? How important is geographic or organizational coverage? How might the lack of cross-functional - or cross-sectional - diversity affect the outcome? What's a useful sampling? Where is the point of diminishing returns? Who will facilitate the sessions: a member of the communication team, an in-house trained facilitator, or a neutral outsider? 5. Widen your scope The answers to many of these questions will partly be determined by the scope of the research. The larger the scope of the issues you're polling for, the larger the panel of groups you'll need to convene. At the same time, remember to ask yourself what you intend to do with the results. Will the sessions be taped, videotaped or otherwise recorded? What kind of qualitative data do you expect to get? Make sure to provide for the resources to analyze the results adequately. 6. Tear up the script, but not the agenda. You'll likely not want to script the sessions. It's important that participants feel free to express themselves without being hemmed in by too much structure. On the other hand, an agenda is essential to make sure you cover the points you need to explore before thanking the group for coming. What are the goals of you and your client? What do you need to ask the group to make sure your survey is as effective as possible? Again, don't forget to listen well, and ask helpful follow-up questions. Measurement tip Focus groups provide a valuable opportunity for participants to talk to you. As they speak, be sure to listen to the language they use, and the way in which they respond to the language in the questions you ask. Think ahead to your survey questions. Are participants using words or terms that you can incorporate into a later survey and that would be more meaningful to them? This article was taken from Strategic Communication Management. ~~~

5 steps to distinguishing corporate responsibility strategy from corporate spin Gary Niekerk, operations manager for corporate responsibility at Intel Corporation, lists five ways to ensure your CR communication is credible: ~~~ Reinforcing established company values the following question was recently posted to The Communicators' Network: Q: How do you drive home corporate values that are already in place? A: When I joined the company, most people were aware of the values, even if they didn't always model them. My colleagues in HR and I switched to a subtler approach aimed at integrating the values into the organization's processes, policies etc. This included: 1. a beefed-up values intranet page that promotes a dedicated values seminar. 2. Values booklets have been edited down and reproduced. Posters and other tools are available via the intranet, on request, and in induction kits. 3. Values have been incorporated into everyone's performance plans, including executives. 4. Values have been included in relevant HR policies. In hindsight, I'd say that developing behaviors that explain the values probably made them more "real." I also think using the values to "sponsor" events and activities is a good way of getting the message across without ramming it down people's throats. Inclusion in performance plans is essential - and it's amazing, but we still have a reasonably steady demand for values booklets - mainly from staff responsible for induction. Tania Angelini, Manager of internal communications, Department of Human Services, Australia ~~~ ALLTEL Sells Text Messaging Wednesday, September 21, 2005 ALLTEL Sells Text MessagingALLTEL, a communications provider in Little Rock, Ark., wanted to improve its sales in text messaging. So the company developed a training program that taught customer service representatives how to transition a customer from resolving his or her problem to selling him or her a text-messaging package. Sales in the month following the training program increased by 30 percent. ALLTEL ranked #77 in the 2005 Training Top 100, Training magazine's annual ranking of organizations that excel at training and development. ~~~ From the 'Are You Serious?' Department: Overweight Employees and Insurance Premiums Some companies are actually starting to concern themselves with their overweight employees' eating habits. Since employees who are overweight theoretically have more health problems, they cost companies more in health insurance premiums. So it makes sense, according to this logic, to encourage heavier employees to trim down a smidge. It may sound nutty, but articles in USA TODAY, The Wall Street Journal and the Chicago Tribune have discussed this topic in recent months, and apparently companies are starting to try it out. All of which means that you might find yourself stuck with designing or even delivering training on healthier lifestyles (read: losing weight). Tom Gilliam, who has written and self-published a book on the topic (Move It. Lose It. Live Healthy, T. Gilliam and Associates LLC, 2005), has a few helpful suggestions. • Be honest with people about the impact of their excess weight. Not a bad idea, but it might be helpful to research that impact and make sure you're not just talking a company line. Nobody will want to hear the news you're bringing, and if you can't show data to prove it's true, you'll probably end up looking like a company shill. • Teach employees the basics of weight loss. • Commit to helping them lose weight. Gilliam suggests structured programs. (Coincidentally, he has his own program, called "Move It. Lose It. Live Healthy.") And programs such as Weight Watchers work with a lot of companies and there's usually a nearby weigh-in site. • Offer incentives. "People like working toward a concrete reward," says Gilliam. "Be creative. Make it fun." Gilliam also suggests that you should also monitor and reward those who have normal BMIs (body-mass indexes) and maintain healthy weights year after year. Yikes. • Get your employees excited about good nutrition. Good luck with this one. If you have to do this, it does make sense to make the workplace as friendly as possible to healthy eating. But you may have a riot on your hands if you try his suggestion about vending machines: "Don't forget to remove all 'junk food' from the premises." He adds, "It's hard to stay on track when vending machines packed with grease and sugar and trans-fatty acids beckon with their sinister glow." • Foster and encourage exercise groups. Learning is social, and so is sticking to a routine. • Link weight loss to larger family issues. Gilliam suggests that you can "use guilt to motivate people by suggesting that their kids are learning bad eating habits by watching them." All we can say is: Proceed with plenty of caution. It's a sensitive enough topic without bringing guilt into the mix. ~~~ Sprint Teaches for Retention Friday, September 16, 2005 Sprint Teaches for RetentionWhen the company realized that turnover in its customer service organization was significant, Sprint started a program called Talentkeepers that taught its leaders practices for better retention. The program reduced turnover in some areas by 40 percent in 2003, and resulted in improved customer satisfaction scores and higher one-call resolution rates. Sprint ranked #4 in the 2005 Training Top 100, Training magazine's annual ranking of organizations that excel at training and development. The Training Top 100 is determined by assessing a range of qualitative and quantitative data, including financial investment in employee development and how closely training efforts are linked to business goals. ~~~ The four keys to coaching success Monday, September 12, 2005 The four keys to coaching successJohn Blakey, director of coaching at LogicaCMG, describes the four critical success factors when coaching was introduced across LogicaCMG, a 21,000-person organization. 1. Create and maintain CEO sponsorship. It's one thing to have an initial conversation with the CEO when coaching is considered innovative and cutting edge. It's another to repeat those conversations when budgets are being reviewed, the initial novelty has gone and the first challenges appear. Sponsorship is like trust; it's hard to win and easily lost. In creating a coaching environment, maintaining CEO sponsorship involves measuring results and reviewing them on a regular basis. It also involves constant innovation to ensure the initiative keeps track with the way the business is evolving. 2. Focus on the "marzipan layer." The idea of trying to create a coaching culture from scratch in a 21,000-person organization is a daunting prospect. Don't try it. These concepts spread by osmosis, not revolution. Focus on people who are in the best position to influence the wider group. In theory, you'd guess this would be the board of the organization, but this group often don't have the time to effectively sponsor this type of initiative. As an alternative, consider the "marzipan layer" - the group of young and ambitious leaders who fill the layer below the board. These leaders are often more enthusiastic about introducing new ideas to the organization and have greater insight into the ambitions of people lower down in the company. 3. Ensure project management discipline. LogicaCMG is steeped in over 30 years of project management discipline. This was a big advantage when building a coaching environment. The required skills include rigorous planning and estimating, active steering groups, regular reporting and communication and celebrating success. Within the coaching team there needs to be sufficient project management skills and aptitude to avoid the inevitable risks these types of programs involve. 4. Create accredited internal coaches. When LogicaCMG initially embarked upon its coaching initiatives we had no option but to involve external coaches. However, our objective was to build an accredited internal team of coaches who could be used alongside external coaches. This wasn't just a cost issue - the benefit of the internal coaching component is that these people can act as change agents within the company in a way that just isn't possible for an external individual. Hence, the final course in our coaching skills training program takes nine months to complete and leads towards accreditation with the International Coach Federation. Source: Strategic HR Review Vol. 4, Issue 5, July/August 2005 ~~~ Introducing a new measurement approach at BP Friday, September 09, 2005 Introducing a new measurement approach at BPIn 2004, the communication team in BP's Lubricants business set out to establish a more rigorous performance management model. Their goal: to produce reliable tracking information to measure the impact of business-crucial communication. The first step was identifying key performance indicators (KPI) to measure the "effects" of communication. Next, they designed a survey to produce answers that feed directly into and inform these KPIs. The project, which was coordinated by Simon Elliott, communication manager at BP Lubricants and Helen Coley-Smith, an independent consultant, resulted in a pioneering approach currently being adopted by the rest of the business. Based on BP's key success factors, here's some suggestions for practitioners working to develop a measurement strategy for their organization:

Source: This extract is from a case study in the latest issue of Strategic Communication Management called "Building a new performance management model at BP." ~~~ Wyeth Teaches ... Ad Management? Wednesday, September 07, 2005 Wyeth Teaches ... Ad Management?Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, based in Collegeville, Pa., solved a company problem with advertising using the right training. Upon realizing that its spending with advertising agencies was way over budget, the company created a program called Ad Agency Management. The program, delivered to product management team members, taught them the principles of managing an ad agency so that they would be able to work more effectively and prudently with other ad agencies. As of 2004, the program had saved Wyeth $77 million. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals ranked #12 in the 2005 Training Top 100, Training magazine's annual ranking of organizations that excel at training and development. The Training Top 100 is determined by assessing a range of qualitative and quantitative data, including financial investment in employee development and how closely training efforts are linked to business goals. ~~~ Motivate employees by getting out of their way A new study of 3.5 million employees by attitude research company, Sirota Survey Intelligence has revealed that workers are more productive when their bosses keep out of their way. Over three-quarters of employees questioned at companies around the world revealed that the obstacles their management throw at them, such as excessive bureaucracy, blame-placing, lack of input into and delays in decision making, interfere with their ability to get their work done quickly and efficiently. Key obstacles include: Excessive bureaucracy – 62% More attention to placing blame than solving problems – 59% Inconsistent management decisions – 57% Wasted time and effort – 56% Lack of input into decision making – 56% Delays in making decisions – 51% Dr David Sirota, chairman emeritus of Sirota Survey Intelligence, comments: “People come to work, to work. Unfortunately, they often find conditions that block high performance, such as excessive bureaucracy burying them in paperwork and slowing decision making to a crawl. Or, they work in an atmosphere where management is consumed with finger-pointing, rather than cooperative problem-solving. Management doesn’t have to motivate employees to perform – it has to help employees perform, which in many cases means getting out of the way.” source ~~~ TOP TIPS: Developing "new model" leaders Business executives are traditionally well-schooled in using tools to meet financial objectives, but they need additional strategies and more information to seek outcomes that more fully take social and environmental impacts into account. What does this mean for leadership development professionals? How can you develop these "new model" leaders? 1. Change the curriculum. New topics could include: understanding diverse stakeholder perspectives, considering what “sustainable development” means for today’s managers, surveying global trends and assessing their impact on management decisions, considering the appropriate role and responsibilities of corporations in an evolving global economy and exploring ways to build partnerships across sectors. 2. It's a journey of discovery. A theme that cuts across all the above topics – and dozens of others that might be added to the list – is that they are not so much about mastery as they are about discovery. Leadership that contributes to a sustainable society is much more about asking questions than it is about finding answers. It’s about honoring the importance of inquiry. 3. Are you asking the right questions? Help executives value inquiry by designing educational experiences that include questions such as: - What is the purpose of our enterprise? - Is it possible to articulate this purpose in a way that engages the passions of employees? - How do we measure success? - What is it that we do as a business when we are at our best that allows us to say that our life has meaning? 4. Getting away from it all. Giving leaders an opportunity for retreat and reflection should be a more prominent component of leadership development initiatives. Retreat is seen as a critical counterpoint to the information overload and speed imperative that govern daily corporate life. It is a source of energy and strength. The common thread of retreat and reflection initiatives should be to move away from the usual daily routines in order to get a different view. 5. Make learning an experience. Experiential learning opportunities for executives – including role-playing, peer exchanges, listening tours and so on – are sources of remarkable breakthroughs in terms of individuals uncovering their own values and understanding others’ points of view. This can mean spending time in their community, with customers or with representatives from different disciplines or functions within a firm. It can also mean discussions across generations or hierarchical layers in a corporation. Source: "Developing leaders for a sustainable society" by Nancy McGaw, Strategic HR Review Vol. 4, Issue 6, Sept/Oct 2005 ~~~ 5 Myths About Changing Behavior Thursday, September 01, 2005 5 Myths About Changing Behavior~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ source ~~~~~~~ Myth 1: Crisis is a powerful impetus for change ~~~~~~~ Reality: Ninety percent of patients who've had coronary bypasses don't sustain changes in the unhealthy lifestyles that worsen their severe heart disease and greatly threaten their lives. ~~~~~~~ Myth 2: Change is motivated by fear ~~~~~~~ Reality: It's too easy for people to go into denial of the bad things that might happen to them. Compelling, positive visions of the future are a much stronger inspiration for change. ~~~~~~~ Myth3: The facts will set us free ~~~~~~~ Reality: Our thinking is guided by narratives, not facts. When a fact doesn't fit our conceptual "frames" -- the metaphors we use to make sense of the world -- we reject it. Also, change is inspired best by emotional appeals rather than factual statements. ~~~~~~~ Myth 4: Small, gradual changes are always easier to make and sustain ~~~~~~~ Reality: Radical, sweeping changes are often easier because they quickly yield benefits. ~~~~~~~ Myth 5: We can't change because our brains become "hardwired" early in life ~~~~~~~ Reality: Our brains have extraordinary "plasticity," meaning that we can continue learning complex new things throughout our lives -- assuming we remain truly active and engaged. ~~~ |

.:Find Me:. If you interested in content, please contact the writer .:acquaintances:.

The Enterprise .:Publications:.

Telegram Buat Dian .:Others:.

The Speech Blog .:New Books:. .:talk about it:.

.:archives:.

.:credits:.

|